Feasibility for clinical trials is all about finding the right sources of data, being able to analyse them and then make decisions for country selection, sites and investigators, as well as patient recruitment strategies. It sounds simple and yet, when it comes to execution it’s very complicated. Therefore feasibility specialists have a lot of questions when choosing the best process for gathering and analysing data. In this article I will focus on the first question:

Which are “the right” sources of data for Feasibility?

The people that have been following me and have read my last article about interviewing 50+ feasibility experts know that I have been looking to identify patterns in the way they do their research and how they optimise their efforts. And every single one of them will tell you that the first definition of “right” data source is ACCURATE.

Accurate comes with a lot more details though. Accurate does not only mean updated. It also means that it’s not misleading. This is why in a lot of cases data coming from national clinical trial registries like clinicaltrials.gov, even though the original data, might also be quite confusing for making final judgement unless you do your homework.

All of these registries have not been created for the purposes we use them. They are for public use to inform about research and its progress. The moment you try to make analysis and get statistical data directly from the source, this brings you to some inconsistencies.

The most common challenge feasibility specialists are facing is when they want to estimate competition or check the completed clinical trials to see their performance. First, you need to do it country by country and second (and most importantly) by choosing one indication, this might bring clinical trials that are including the indication not necessarily in the focus of research but rather as comorbidity or something else.

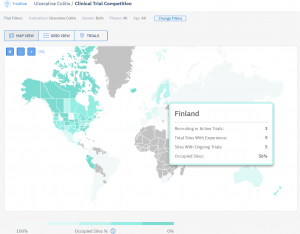

Another definition of “right” data is MEANINGFUL. Meaningful is key, especially in clinical research organisations (CROs) where they have fewer than 10 days to run a feasibility assessment (Request-a-Proposal). Usually, a big amount of data is being consumed in the form of a map or graph. In the case of Competition analysis, a lot of specialists find it easy and fast to create a map where you see the number of trials per country. This is a good indicator of how much research is being done in a given region, yet, quite misleading if you are looking for selecting a country for its capacity. In this case, what you should be doing is looking for the “pressure” in the country a.k.a how much research is being done in the experienced sites.

This is for example how TrialHub compares Countries based on the Percentage of Occupied Sites in the Country.

The “right” type of feasibility data is also ALL-ENCOMPASSING. Another point of struggle for feasibility specialists is when they need to compare their historical experience information with the data coming from the outside world.

This means they have to check two (and in most cases many more than that) platforms and websites in order to get all the data. This not only takes time but it also costs a lot of effort and can lead to mistakes when transferring the data from one place to another. Therefore a lot of companies go with the data they have inhouse in most cases and only if they don’t have anything in place, will they try to gather information from other sources.

This is far from perfect – said one of the Strategic Feasibility Directors from a top 5 CRO.

Of course, there are plenty of examples of companies that have created multi-source sophisticated feasibility platforms that avoid this hurdle and are used for a more centralised approach. You can have a look at an old article I wrote about Novartis and AstraZeneca as an example.

There is a lot to be said about data sources in Feasibility. Not to mention the Feasibility I am referring to is all related to indication feasibility and I haven’t even scratched the surface of Sites & Investigators and Patient Journey data. The most complicated part comes when we start talking about the more subjective types of information we need to gather too (like investigator fees, patient motivation etc.) which I will focus on in the next Part 2.